The Beginning, Middle and End: Where to Find Them in Your Novel

The Beginning, Middle and End: Where to Find Them in Your Novel

Writing a novel is a daunting task. There are so many things to consider before committing even a single word to that intimidating blank screen. What is the main line of action? How many subplots do I have? Who is the main character? Who are the supporting characters? What is the theme? The tone? The setting? How many settings? When does it take place? Why am I doing this? How stupid was I to think I could do this?! How in the holy hell am I going to get 90,000 words out of this stupid time travel space opera love story idea?!?!?!?!?!

Relax. Breathe. Have a cup of tea.

Okay, now that we have that out of the way, I’m here to tell you something that will either be heavenly in its comfort or give you hell-raising anxiety.

There is no right or wrong way. Whatever way works best for you is the way you should work. The way that works best for me is discovering the beginning, middle, and end. I have written and self-published two YA novels (The Salem Witches: The Fifth Point of the Pentagram and The Salem Witches Book II: Born Again) and I’m currently working on the third book of the trilogy. I have a handful of book ideas for the future ranging from science fiction and fantasy to action adventure and a political thriller. Over the course of writing my first two books, I have found a way that works for me in getting a solid story together that is coherent, and entertaining.

I use the principle of Keyframing.

My background is in animation and keyframing is one of the core principles of that artform. When you watch an animated film, the actions of characters are almost always keyframed. That means the animator posed the character at the beginning of an action and then at the end of an action. Those are the keyframes. The animator might add a keyframe that represents the halfway point of the motion before charting out how quickly the action moves, thus determining the number of in-between frames to get from one keyframe to the next. Character animation almost never happens straight ahead where an animator starts at frame-one and takes however many frames to get to the end of the motion. An animator always knows before even starting the work where the motion starts where it stops and how long it needs to take to get there.

I took those principles and applied them to my writing. For me, before my writing process even begins, I need to know how the story starts and how it ends. I am also a disciple of the Hero’s Journey, which can absolutely be applied to novel writing as easily as it can be applied to screenwriting. That being the case, I determine what the midpoint of the story is. I also apply the idea of 3-Act Structure to my novel writing so the end of Act I is another keyframe and the end of Act II is another. That gives me five keyframes at the beginning of my process to work with. I don’t consider the entire novel as one big story at that point. I need to fill in the in-betweens that get me from one keyframe, or plot point, to the next.

If Beginning, Middle, and End are the three most important words in constructing a story, the next three most important words for me are...

Outline, Outline, and Outline.

Outlining is not for everyone. I get it. A lot of writers just dive into the story and see where it takes them. We will meet a writer below who does that. If that is your process, and if that works for you, God bless. Personally, I get lost writing that way. My father was a homebuilder, and you can’t build a home without a blueprint. Like a homebuilder builds a house, a writer builds a story, and the outline is the writer’s blueprint.

The outline can be as detailed or as general as you want it to be, but it is a critical tool in discovering your beginning, middle, and end. I took a 6-week novel writing class years ago and the purpose of the class was to get us to write the first chapter of a book we could eventually finish. At the end of the session, I had that first chapter, but I had no idea where to go from there. I had never written a novel, so I didn’t know what the process was. It took me a beat, but I realized that I could make up my own process, so that’s what I did. I had never written a novel, but I had written several screenplays. A screenplay is often a condensed version of a novel. Another way to look at a screenplay in screenplay format is that it looks an awful lot like an outline. So, I wrote my first novel first as a screenplay. I wrote a few drafts of it, and I made sure the story worked, that it was structured the way I wanted it to be, and that the characters all fit their roles. Once I felt comfortable, I started writing the novel and working on it part-time, I wrote 90,000 words in about three weeks.

I also wrote a screenplay version first of my second novel but skipped multiple rewrites. I wrote a first draft and then gave it one more pass to make sure the story worked. Comfortable that it did, I set out to write it in novel form. Writing it as a screenplay allowed me to find the structure of the story. I had the traditional act breaks that revealed my beginning, middle, and end. The individual scenes of the script were turned into the chapters of the novel, with some added material as I went along. A screenplay is a relatively restricted space in terms of how much you can write. Less is always more. But a novel allows that universe to rapidly expand. Having the framework of the story written out in a screenplay, or other form of outline, allows me to expand on it in ways that make sense and fit within the framework of the story I’ve already created, thus allowing me to be even more creative within that framework.

That is a process that works for me, but I’m not tyrannical enough to demand that it should work for everyone. Diana Knightly has found much success as a self-published author and her process is upside down from what I do. She has self-published 15 novels.

I asked her about her development process, and I thought her answer was very interesting.

“I begin with wanting to answer a question, usually in the form of a challenge: For Kaitlyn and the Highlander it was: Can I make a time travel story that feels so realistic that a reader might believe it happened in that place? And: If a Hero is out of time, can he be vulnerable and still heroic? I mull over the challenge a bit, usually I have a visual idea that comes to me, like a movie I ‘see’ it in my mind. For Kaitlyn and the Highlander, it was a dark stormy night on Fernandina Beach, and then a time traveler’s leather boot steps onto the sand, he climbs the stairs of the wooden walkway, and thuds down the planks, headed to the back door — inside is a raging drunken house party. For one of the books, I started visualizing the main character, Kaitlyn, holding the hand of a young boy… the visual came to me before I realized who the kid was, and it stuck with me for a couple of books before it was written into the story.”

That is a much more ambiguous way to construct a universe than I would be comfortable with, but it works very well for Diana. Not only that, but I asked her about outlining, and to be honest, after hearing her first answer, I wasn’t surprised by this one.

“I don’t outline at all, I just start with that challenge, visual, and vibe and start telling myself the story. It’s a little stream of consciousness. I let the characters go where they will and do what they say. It’s created many surprises; my favorite was when I was writing a book called Violet’s Mountain about a young woman and the two brothers who love her. I thought she was going to end up with the younger brother. The challenge was, could I tell a fairytale where the beautiful princess is won by the second brother, but then before I was aware, she and the oldest brother are professing their love to each other. I had written half the book without knowing who the real Hero was.”

So clearly, Diana’s writing process is faster and looser than mine. That was confirmed when I asked her if she adheres to any kind of story structure.

“No, I just wing it. I think that growing up as an avid reader and huge fan of movies, I just get a feel for the wind-up, the peak, and then the final act, but most of the time I just realize that the scene I’m about to write will be the ending scene. I’ve accomplished the challenge goal. (I’m writing in a long series, so I can end on a cliff if that’s necessary.) I sense that the next scene will be a new story. But… I do write fast and as I write I have two mantras, one, Get Weirder Faster, and two, Drive Your Heroine up a Tree and then Throw Rocks at Her. It keeps the story exciting.”

So, while she might not necessarily adhere to a structure, Diana still has mantras, practices, and storytelling philosophies she works by.

The point of all of this is to encourage you not to be intimidated.

I have a process for finding the beginning, middle, and end of a story that works well for me and Diana has a process that works well for her. Through trial and error, you will find a process that works well for you.

I will leave you with this. It’s really quite simple. Every great story is about a person who wants something, but someone or something stands as an obstacle to prevent her from getting it. Ask yourself these questions: Who is my main character? What does she want? Who is trying to stop her from getting it? Once you’ve done that, fill in the blanks of the following sentence: “This is a story about __________, who after ___________, wants desperately to ___________.” That’s your story.

The beginning is where the character is. The end is where she wants to be. The middle is how she gets there.

Happy writing!

Let's hear your thoughts in the comments below!

Got an idea for a post? Or have you collaborated with Stage 32 members to create a project? We'd love to hear about it. Email Ashley at blog@stage32.com and let's get your post published!

Please help support your fellow Stage 32ers by sharing this on social. Check out the social media buttons at the top to share on Instagram @stage32 , Twitter @stage32 , Facebook @stage32 , and LinkedIn @stage-32 .

About the Author

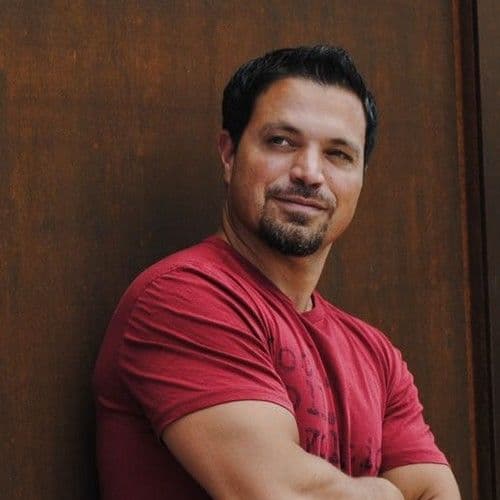

Brian Smith

Production Manager, Screenwriter, Script Consultant

Brian has been a professional screenplay reader since 2006, and has written coverage for over 1,000 scripts and books for companies such as Walden Media and Scott Free Films. Scripts and books that Brian has read and covered include Twilight, Touristas, Nim’s Island, Hotel for Dogs, and Inkheart. Br...