3 Lessons in Story Proportion from Working Across Mediums

3 Lessons in Story Proportion from Working Across Mediums

If you’re taking your career as a writer seriously, you’ve probably spent a fair amount of time studying the craft. You’ve read the books—Save the Cat, maybe some Truby or Syd Field. You’ve taken the webinars, maybe even an online course or two. You understand story beats and character arcs and you have a solid sense of how to put the pieces together.

But maybe you’ve hit a plateau. Technically, your story works—yet somehow, it doesn’t sing.

If you’ve read my other posts, you know I’m a structure girl. I love watching excellent writers use structure as the most elegant vehicle for their ideas. But the truth is, structure – while it’s absolutely essential – isn’t enough.

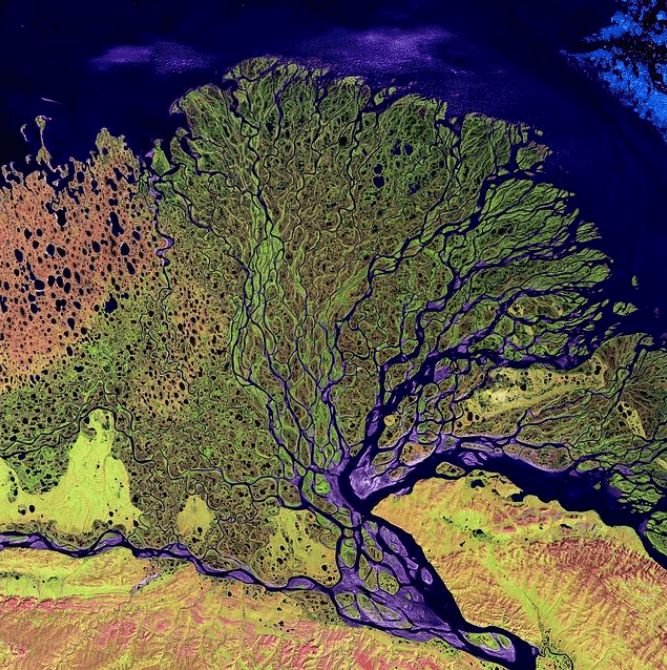

Mastery-level storytelling depends on something much harder to define than plot points. That’s because it’s not something you do on the page; it’s something you develop inside yourself. It’s your intuitive sense for the four key elements of beautiful storytelling: proportion, pattern, harmony, and order.

It’s like training your ear to hear the strains of a symphony: the motifs, the way the different instruments carry themes and hand them off, the balance of voices, and the way the different musical threads weave together to form a whole.

This isn’t about knowing you need a key change at minute five—or an inciting incident at ten percent. It’s about understanding why you need it, instinctively. That intuitive sense is the difference between narrative-by-the-beats and a story that sings.

I call this intuition your ‘story sense’, and I’m developing a method to help you train it*.* In this article, we’ll focus on how you can use cross-medium storytelling to train one of its core principles: proportion**.**

Lesson 1: Short Stories and Narrative Economy

In The Poetics—the original rulebook for dramatic writing—Aristotle says:

“Now as for magnitude, in order to be beautiful, a living creature or anything else made up of parts must not only have its parts organized, but must also be of an appropriate magnitude. Beauty depends on magnitude and order.”

He goes on to explain that the right measure of magnitude is whatever allows the full expression of the plot—and that the plot, in turn, must be clear.

Notice that Aristotle doesn’t give you a page count or a word count. Instead, he invites you to consider the proportion between the plot and the length of the story**.**

When confronted with the problem of proportion, some modern storycraft experts will counsel you to solve this by the numbers. Sean Coyne calls 2,000-word chapters “potato chip length,” and Save the Cat even has a beat-mapper calculator that will literally divide your story for you. Those metrics can be helpful—but Aristotle (and I) invite you to go deeper: to train your intuitive sense for the proportion between your story’s emotional and thematic weight and its length.

A short story demonstrates the principle of story proportion in miniature. You have one small canvas and must fit the entire emotional universe onto it. There’s no room for narrative fat; every sentence has to do several jobs at once.

Writing short fiction trains you to feel when a moment has reached its right length, when a scene has given all it can, and when to stop before the emotion thins.

Like lyric poetry, the short story teaches you that a strong narrative isn’t about how much you write, but how impactfully you communicate meaning and emotional depth.

When you return to screenwriting after this kind of training, you’ll have a much more refined sense for how to maximize every beat for the good of the whole.

Proportion principle: In the short form, you learn that less isn’t loss—it’s precision.

Try it: write a 300-word short story or a poem. Then read it aloud. Does every line earn its place? That’s your story sense calibrating in real time.

Lesson 2: Short Films and Cinematic Precision

If the short story teaches you to hear proportion, the short film lets you see it. A short film is the economy of the short story made visible. Like the short story, you get one governing idea, one emotional promise, one complete arc–but the short film teaches you how to use visuals to speak volumes.

Working in this form forces you to tune your intuition for visual proportion, especially if you’re not just writing the script, but actually shooting the film. You learn how to make every shot serve the core theme – and how to choose the right shot for what you want to communicate. You also begin to see how pacing, composition, and silence balance the story equation, and how the music can supply another layer of meaning.

The Albanian short Don’t Judge by Elvis Naci is an excellent example of this principle of proportion as cinematic precision. It’s only four minutes long, yet it delivers the emotional impact of a feature. Characters, relationships, and conflict are conveyed in brilliant shorthand. And even though it packs a punch, the story’s length is exactly right for its idea—no more, no less.

When you hone your craft on this level of precision, it only makes you a stronger storyteller when you return to your own projects. You’ll begin to see the proportions of your story not just in terms of the words on the page, but you’ll also develop your intuitive sense for the language of visuals.

Proportion principle: In the short film, you learn how to extend your sense of proportion and balance to include visual elements and sound.

Try it: Start with writing a short film script, and then experiment with an AV script. How would you tell your story visually? What shots do you need to deliver maximum impact? How do you keep the pacing moving while allowing enough time for the beats to land?

Lesson 3: The Novel and Expansive Scope

If short forms teach the proportions that come with narrative compression, the novel teaches you how to expand your story without sacrificing depth or losing a grip on narrative precision and economy.

This can be a real challenge. We can feel like we have all the space in the world. I once heard someone who was coming from screenwriting into novels say that it “wasn’t fair” – novelists can go inside characters’ heads and they don’t have to worry so much about rigid page counts.

But that kind of freedom can be dangerous if you lose grip on the principle of proportionality.

Writing long-form stretches your sense of proportion outward. Most writers understand those familiar percentage markers where Things of Story Significance happen—and that they work roughly the same whether you’re writing flash fiction or a thousand-page novel. But those ratios are not the only proportions operating in a story. I often see novelists lose the sense of proportion on the level of the scene or the chapter, or in the development of key characters.

Too much happens in a chapter, or not enough. Or the writer engages in random acts of narrative—like sprinkling in unnecessary backstory or internal dialogue—in the hopes that this creates character depth, when really this just unbalances the character’s development.

When a novel keeps us too much at a 30,000 foot narrative view without dropping us into a character’s lived experience, we disconnect. Spend too long inside a character’s head and we lose our sense of the whole.

Whenever and wherever we find the story out of balance, we’re dealing with a problem of proportion.

This is something you have to learn how to feel, not measure. By learning how much space each event deserves, when to zoom in, and when to pull back, novelists train their sense of narrative proportion**.**

When screenwriters explore this, they develop their own instinct for scale: when a feature wants to breathe into a series, or when restraint will make the story stronger.

I’ve tried to architect my way through more stories than I can count. I thought if I just had the right spreadsheet or beat sheet or just played it by the numbers, the story would work. But no spreadsheet can track your intuitive sense of why a story works—and when I finally learned to trust that intuition, my writing leveled up. Like Luke Skywalker learning to use the Force under Obi-Wan Kenobi’s guidance, you have to practice trusting your own story sense.

You can do that by trying your hand at storytelling in different mediums, and you can also do it by reading master storytellers and watching master filmmakers. Study how they do what they do, and feel into the proportions and the balance of the story.

Proportion principle: The larger the canvas, the more care the composition requires.

Try it: If writing a novel isn’t in your immediate future, remember that you can learn by reading and observation. One of my favorite classic novels (and I think a masterclass in proportion and structure) is Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities. Whatever novel you choose, just remember to pay attention to what really works and what feels off.

Expanding Your Story Sense

Whether you’ve written a short story, filmed a four-minute short, or studied a great novel, you’ve been training your internal gauge for story proportion and balance. As Aristotle tells us, a story’s beauty depends on its magnitude and order. In other words, the scope of the story should determine its form**.**

You can come at this in two ways. You can start with the form—“I want to write a novel”—and then find a story large enough to fill that space. Or you can start with the idea and ask, “What vessel will best contain this? Would it live most naturally as a short story, a novella, a feature script, or a series?”

Either way, learning to feel that relationship between scope and structure is the essence of story proportion**.**

Working across mediums trains this sense. Each form teaches you something about magnitude—what expands, what compresses, and what balance feels just right.

In next month’s article, I’ll take this one step further and look at what happens when you adapt the same idea across multiple mediums. What stays? What has to change? And what does that process reveal about the proportional relationship between a story’s medium and its expression?

The more you practice this, the more you’ll begin to get a feel for what I call “story math”—an intuitive sense for how to balance all of the different elements of a story so that they come together in an impactful and harmonious whole. So try shifting narrative gears and see what you discover— and how it makes you a better screenwriter when you return.

Let's hear your thoughts in the comments below!

Got an idea for a post? Or have you collaborated with Stage 32 members to create a project? We'd love to hear about it. Email Ashley at blog@stage32.com and let's get your post published!

Please help support your fellow Stage 32ers by sharing this on social. Check out the social media buttons at the top to share on Instagram @stage32 , Twitter @stage32 , Facebook @stage32 , and LinkedIn @stage-32 .

About the Author

Shannon K. Valenzuela

Author, Screenwriter

S.K. is a screenwriter, author, and editor. Writing is in her blood and she's been penning stories since she was in grade school, but she decided to take an academic track out of college. She received her Ph.D. in Medieval Literature from the University of Notre Dame and has spent many years teac...